"Waltzing with Brando" is a fun and breezy critique of late-stage capitalism

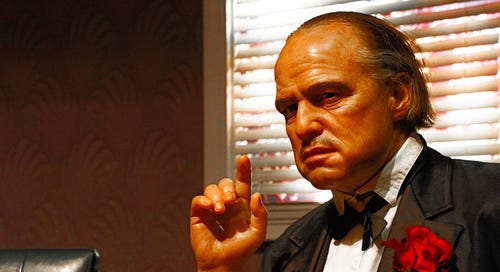

Billy Zane steals the show as a charming, mischievous, and idealistic Hollywood legend.

Between 1969 and 1974, Hollywood megastar Marlon Brando made two of his most famous movies, The Godfather and Last Tango in Paris. During this same period, he worked with architect Bernard Judge in his adopted country of Tahiti to create a paradise getaway.

Waltzing with Brando tells the story of how Brando did both of these things at the same time. Yet even though Hollywood is notorious for navel-gazing (How many Best Picture winners focus on the entertainment business?), Waltzing with Brando clearly finds the architecture narrative more compelling than the cinematic one.

This is appropriate for two reasons: First, that is how Brando himself felt about the work he was doing at the time; and second, Brando’s paradise getaway wasn’t some celebrity vanity project. Brando was a left-winger through and through, openly throwing his considerable clout behind African American civil rights, Native American civil rights, anti-imperialism initiatives, gender equality (including LGBTQ+ rights), and labor union mobilization.

Perhaps most importantly, at least in terms of his vision for a Tahiti resort, Brando understood that real estate development does not need to destroy local ecosystems and historical sites. Hence Waltzing with Brando’s iteration of Brando (Billy Zane) recruits Judge (Jon Heder) in a movie brought to life by the directing and writing of auteur Bill Fishman (My Dinner with Jimi).

Waltzing with Brando is, therefore, not the standard Hollywood biopic that glorifies the entertainment industry and celebrates its excesses. Like Brando himself, the movie centers political issues like the horrors of colonialism and humanity’s rapid destruction of our planet. When Heder’s Judge explains to Brando that he is an eco-friendly architect because “Earth is our most precious resource, and we have to protect it vigorously,” Zane’s Brando warmly smiles because he recognizes a kindred spirit. After immersing himself in a world of ass-kissing phonies, Zane’s Brando sees in Judge’s Heder a fellow idealist and genuine intellectual.

The chemistry between Zane and Heder provides Waltzing with Brando with its beating heart. Zane doesn’t so much play Brando as resurrect him, confidently reminding audiences of Brando’s iconic mannerisms without ever seeming like a caricature. Heder similarly embodies Judge, a man whose enthusiasm and progressivism were every bit as authentic as Brando’s. Like a jaunty waltz, the movie’s tone is light and breezy, happily bouncing between plot points with lengthy pauses to explore the ideas and personalities that animated Brando’s ambitious project. Brando and Judge were the kinds of people who learned about the Ghyben-Herzberg lens — a lens-shaped body of fresh groundwater that floats atop dense saltwater on coastal aquifers and islands — and became immediately excited.

Why? Because it made it possible for their planned permanent Brando home to be both environmentally sound and self-sustaining.

It is unclear whether Brando was familiar with the later works of philosopher and economist Karl Marx, but if so, he would have certainly known that Marx had these same views on economics and ecology. Per Dr. Kohei Saito, a philosopher at the University of Tokyo who has written about Marx’s environmental views:

As Marx started to study natural sciences later in the 1850s and 1860s, he came to realize the development of technologies in capitalism actually don't create a condition for emancipation of the working class. Because not only do those technologies control the workers more efficiently, they destabilize the old system of jobs and make more precarious, low skilled jobs. At the same time those technologies exploit from nature more efficiently and create various problems such as exhaustion of the soil, massive deforestation, and the exhaustion of the fuels, and so on.

Marx came to realize that this kind of technology undermines material conditions for sustainable development of human beings. And the central concept for Mark at that time in the sixties is metabolism. He thinks that this metabolic interaction between humans and nature is quite essential for any kind of society, but the problem of capitalism is it really transforms and organizes this entire metabolism between humans and nature for the sake of profit-making. Technologies are also used for this purpose. So technologies are not for the purpose of creating better life, free time and sustainable production, but rather it exploits workers and nature at the same time for the sake of more growth, more profit, and so on.

I won’t dare spoil how this movie explores these themes, or far that matter divulge any of the other myriad pleasures contained within Waltzing with Brando. Due for release in the US in September, but already having premiered at the Torino Film Festival in November, Waltzing with Brando will hopefully generate buzz as a rare movie with an intelligent message and a stellar cast (including Richard Dreyfuss, Camille Razat, Alaina Huffman, and Tia Carrere).

Brando was ahead of his time in appreciating the moral horrors of racism, sexism, imperialism, and ecological destruction. He hoped, through his resort, to demonstrate that a better way is possible. If this film takes off, perhaps others will see the same thing.

Fishman, Zane, Heder, and their colleagues certainly have done their best in creating this entertaining, informative, and rewatchable gem.

Back Seat Socialism

Column by Matthew Rozsa who is a professional journalist for more than 13 years. Currently he is writing a book for Beacon Press, "Neurosocialism," which argues that autistic people like the author struggle under capitalism, and explains how neurosocialism - the distinct anticapitalist perspective one develops by living as a neurodiverse individual - can be an important organizing principle for the left.