"Just Plain Common Sense": Great liberals like FDR supported free trade, and must continue to do so

I review humanity's collective intellectual history to explain why.

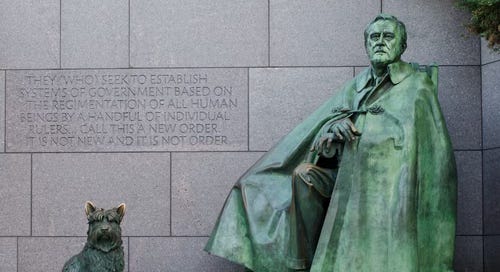

I’m not going out on a limb when I declare Franklin D. Roosevelt as one of liberals’ favorite presidents.

From successfully fighting poverty for generations with his New Deal programs and defeating the Nazis during World War II to creating an enduring and diverse political coalition, the so-called FDR is one of a handful of American presidents that critics of capitalism can claim as their own, even though Roosevelt was himself a capitalist. To this day, prominent left-wing politicians like Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York frequently cite FDR as an inspiration.

For this reason, I want to share a passage from Roosevelt’s 1944 State of the Union message. It pertains to an issue where many modern leftists disagree with FDR — the importance of free trade.

“There are people who burrow through our Nation like unseeing moles, and attempt to spread the suspicion that if other Nations are encouraged to raise their standards of living, our own American standard of living must of necessity be depressed,” Roosevelt said. “The fact is the very contrary. It has been shown time and again that if the standard of living of any country goes up, so does its purchasing power — and that such a rise encourages a better standard of living in neighboring countries with whom it trades.”

Roosevelt concluded this section of his speech by adding, “That is just plain common sense.”

As President Donald Trump crashes his tariffs through the American and global economies like a proverbial wrecking ball, liberals need to return to their Rooseveltian roots. They need to accept that — as the key to any effective economic policy that helps the struggling classes — we should support low tariffs, not high tariffs.

To explore this theme, I interviewed Ed Gresser, the Progressive Policy Institute’s vice president and director for trade and global markets. He also wrote the 2007 book “Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy,” which directly inspired me to both embrace free trade and write my Rutgers master’s thesis about President Grover Cleveland’s pro-trade 1887 State of the Union message.

The below interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity (and the interviewer’s occasional mispronunciations of foreign names).

Something I found really fascinating in your book is how economists, as far back as ancient Greece and ancient China, understood the basic dynamics of macroeconomics and why free trade is ultimately more capable of sustaining prosperity. Why do you think these ideas and the history of these ideas aren't better known?

That's a good question. I would guess people who go into classics of various sorts, they're typically not economists, and that's not what's of most interest to them. They're literary or historical minded people. I think most people who think about economics sort of feel it kind of gets its start in the 18th century, with Adam Smith and mercantilism and whatnot. Yet there is a kind of interesting long history of people thinking, how do you get more things more cheaply? They had good ideas about it, even if they didn't have the mathematics and the apparatus that economists do now.

How familiar is Xenophon, in general in terms of classical philosophers? He said, “Now the greater number of people attracted to Athens, clearly the greater the development of imports and exports. More goods will be sent out of the country, there will be more buying and selling, with a consequent influx of money in rents to individuals and customs dues for the state.”

He's a very well-known name, but not particularly for philosophy. He wrote a couple of history books that are widely read about Athens after the Peloponnesian War and the war with Persia. But his non-historical stuff is much less well-known.

I'm going to read part of a quote from the ancient Chinese intellectual Sima Qian: “Cheap goods will go where they fetch more, while expensive goods will make men's search for cheap ones. When all work willingly at their trades, just as water flows ceaselessly downhill, day and night, things will appear unsought and people will produce them without being asked.”

What I find intriguing about that observation is that it was written under a monarchy. People often assume that free trade relies on free societies, but it seems like these basic economic principles apply regardless of whether you're talking about free societies or totalitarian societies. I'm curious if you can elaborate on why that is the case.

Sima Qian was a genius. In Chinese classics, he would be an A-list name. It would be well above Xenophon on the Western lists. Sima Qian basically invented Chinese history, kind of like Herodotus and Thucydides did for Western history. Just a really brilliant writer with lots of insights on power in government and lots of very interesting personal stories about the early Chinese people, of various sorts.

I would probably think the society he was living in would not be considered a totalitarian society. It would be a monarchy and not have democratic characteristics at all, but not a society with no independent institutions or autonomous institutions and no freedom of thought. There was obviously a high intellectual society in China in those days and very good historical record keeping. There was some interesting science going on, and I think if you sort of transfer that to Western countries, there were definitely authoritarian places where you also have a lot of kind of high quality intellectual work.

I'm now going to skip ahead. My next question is going to be about one of my favorite figures from history, British PM and diplomat Richard Cobden. You quote him after he signed the Anglo-French Agreement in 1860 saying, “The speculative philosopher of a thousand years hence will date the greatest revolution that ever happened in the world's history from the triumph of the principle which we have met here to advocate.”

Now, obviously that did not prove prophetic, but my question is, do you think it is still plausible that world peace on a grand scale as envisioned by Cobden that could occur through a series of interlocking trade agreements?

I probably would have a kind of more modest view of that. I think that Cobden and Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of State, Cordell Hull, had a very strong view that countries which trade freely with one another are linked to one another as customers and as suppliers, and are mutually benefiting from this, that rationally that makes wars between them less likely. It creates constituencies that would like to get the governments to get along.

But it's also true that economic benefits and rational calculations are only part of government's thinking and part of public opinion. They're not all of it. And sometimes there are things that are more important in the government’s mind, or the public’s mind, that lead to conflict anyway. I think of trade as something that is stabilizing and makes peaceful relations among neighbors and big countries more likely, but not inevitable.

My last question, and this goes to the heart of your book — and I by the way, acknowledge that the book is mostly about American liberalism and the global economy, I'm focusing more on the intellectual history because to me that's an under-explored question — I want to hear you now answer is. Franklin Roosevelt in his 1944 State of the Union pointed out that it “seems to be common sense” to support free trade, but even though liberals for decades pegged their arguments about trade policy on Roosevelt's premise, that notion now seems to be verboten in some left-wing communities. And I'm curious in your mind, what can be done to re-convince liberals of the wisdom of Roosevelt's observation?

I guess it's sort of bittersweet, but I think Trump is doing this. If you look at polling right now, liberals in general are very anti-tariff, and self-described Democrats, likewise. I think public opinion is actually changing as people see what the alternative really looks like.

That's not going to be enough to prevent a lot of damage coming from the Trump administration, but I think it is clearly the mood among Democrats and liberals right now. Tariffs aren't a really good idea at all. It would be, I think, valuable for groups like PPI or writers like yourself to remind people that there is a really strong and very intellectually powerful liberal tradition that thought about these things before and came up with a lot of good ideas.

Back Seat Socialism

Column by Matthew Rozsa who is a professional journalist for more than 13 years. Currently he is writing a book for Beacon Press, "Neurosocialism," which argues that autistic people like the author struggle under capitalism, and explains how neurosocialism - the distinct anticapitalist perspective one develops by living as a neurodiverse individual - can be an important organizing principle for the left.