There’s a kind of digital abuse you don’t notice until you’re inside it.

My first encounter was with an automated call system: the voice polite, the script thorough, the options neat—yet each choice narrowed me into categories that didn’t fit. “Zero” for an operator did nothing. It was like shouting into a void—present, speaking, and somehow still not there. It doesn’t arrive with force, but with persistence—intrusions that teach you, over time, your consent is optional. In the moment, it feels like nothing; only later do you register the aftertaste: a slip in your defenses, an intrusion disguised as normal.

That call system taught me the template: options as ceremony, routing as law, delay as enforcement. Escalation is taxed until it dies; the system only recognizes problems it has budgeted for. Anything outside that map is redirected until it disappears. On paper, you had a choice; in practice, your boundary was treated as a cost to be engineered away.

Online, I began to see the same template everywhere. In the mid-2000s, autoplay videos re-enabled themselves after you shut them off. Email “preferences” flipped back on after updates. Privacy settings, once buried in menus, would reset after a redesign. At first, you could tell yourself it was a bug or a fluke. But the pattern repeated until it was unmistakable: not an accident, but the model.

Over time, it left a mark: a slow loss of self and control, the sense that your place in the system was always provisional—a bruise that fades just long enough for you to forget, then returns in a different interface with the same pressure.

We’ve already lived through three acts of the same play.

Act I: Ad blocking. Installing a blocker once felt like a clean win: pages loaded faster, pop-ups vanished, the sense of being watched eased. But publishers built anti-adblock walls, ads slipped in as “native” content, and trackers moved into invisible channels. When blockers still worked too well, Chrome’s Manifest V3 weakened them further. Refusal didn’t stop extraction; it taught the system how to extract differently.

Act II: Do Not Track. Around 2010, browsers offered a polite request: “Please don’t follow me.” Compliance was voluntary, and the big players ignored it. Tracking migrated from cookies to device fingerprinting and stitched identities. Even Apple’s “App Tracking Transparency” didn’t stop the underlying economy—Meta used dark patterns to push “agree” and redefined tracking as measurement so data kept flowing. Again, “no” was just a routing instruction.

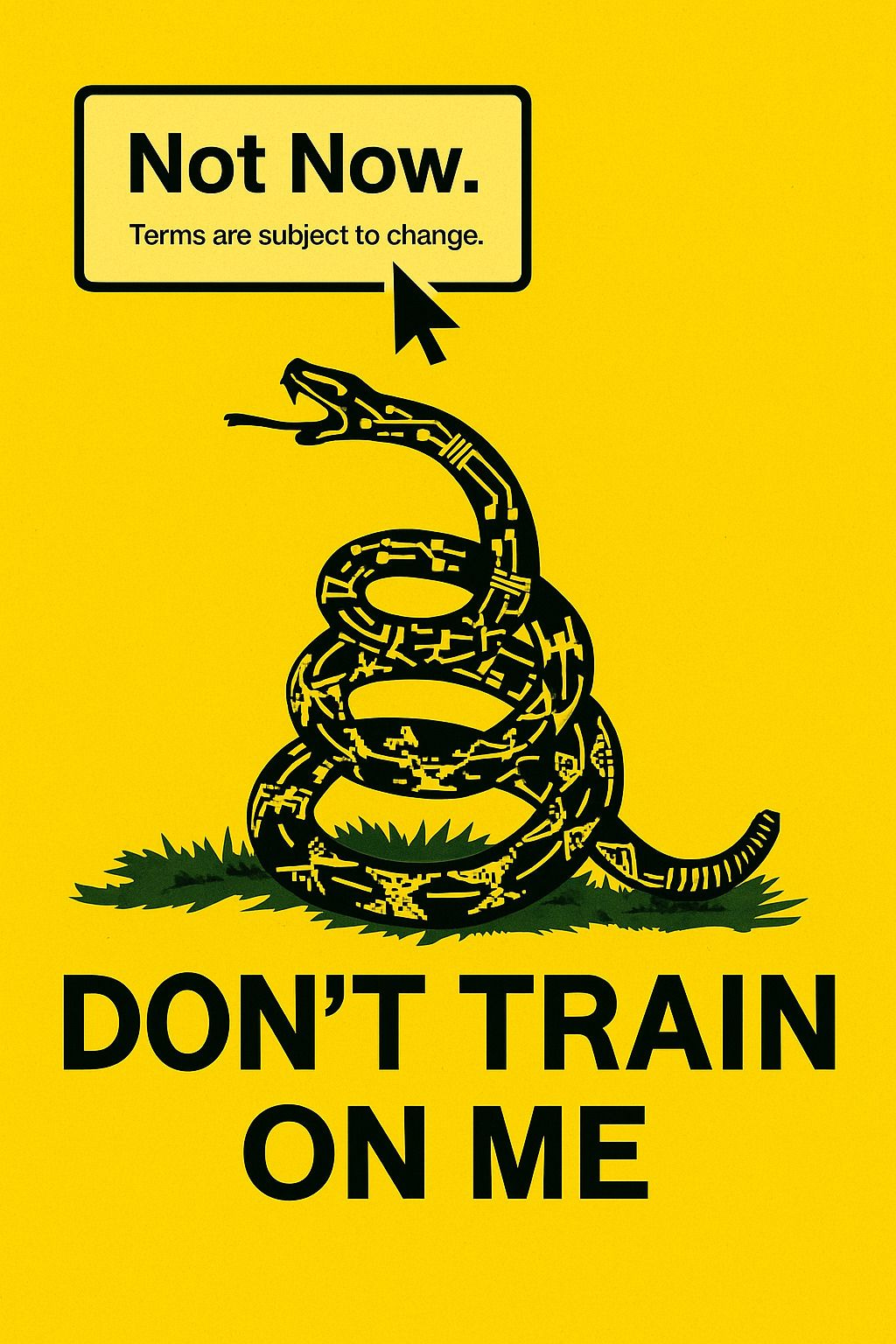

Act III: Don’t train on my data. In the 2020s, the promise is to keep your voice and style out of the model’s mouth. The moves are the same, only scaled: scraping from mirrors and caches, leaking paywalls, repackaging datasets. Watermarks are stripped or ignored. Even when a setting is honored, there’s no universal enforcement, and unlearning is rare and costly. The “no” still isn’t an endpoint—just another signal for how to keep going.

In every act, the rituals repeat: click “No,” flip the toggles, watch the ground shift. A feature refuses to work unless you concede. A “Not now” button replaces “No.” Menus reorder, old paths disappear. You aren’t adopting features; you’re being conscripted into a roadmap.

AI raises the stakes because the bruise is no longer about being handled—it’s about being replaced.

Extraction now stops at nothing less than imitation: your cadence, your style, your gestures—turned into parameters. Where ad tech made you visible to buyers, model training can make you optional to them. A version of you exists without you, summoned on demand, confident and hollow. Each output—an email in your tone, a portrait in your style—is ventriloquism dressed as assistance, flattering until it takes your place.

One scrape spawns a thousand derivatives. Training is opaque, provenance blurs, unlearning is partial at best. You can delete a post, but your voice remains in the weights. Companies claim they didn’t train on your file—because they trained on a mirror, a cache, or a synthetic clone. “Style transfer” becomes the euphemism for appropriation.

And the economics flip: where visibility once raised your value, imitation erodes it. Credit is optional, payment exceptional, and permission something added after the fact. The operating principle hasn’t changed: consent is an obstacle, respect is discretionary, and the constitution is written for profit. We don’t just live in private platforms; we live under private governments, where the law is the business model and the citizen is the product.

In the offline world, erosion of rights moves slowly—measured in years of policy shifts, regulatory rollbacks, or corporate mergers. You might notice when a neighborhood library closes, when public transit raises fares, when a park is fenced off. On the internet, the same erosion happens at the speed of an update. One morning a feature is free; by evening it’s throttled, paywalled, or gone. The cost is the same: a public space quietly privatized, a common good turned into a gated one. The difference is pace. Online, rights don’t decay—they vanish.

In private governments, the master key is four words: terms subject to change. It’s the clause that voids every safeguard the moment it becomes inconvenient, the magic spell that turns “no” into “not anymore,” “private” into “shared for your benefit,” and “included” into “now behind a paywall.” It makes every right revocable, every promise conditional, every win temporary. A real digital democracy would lock that door—decisions are made with the public, not for them; not by silent updates to the code or the fine print.

Beyond Toggles: Building Digital Democracy

Respect can’t be a setting you have to keep turning back on. It has to be built into the constitution of the platform—limits no CEO, update, or profit motive can cross.

Law can draw those limits: make “public” mean licensed, not free to harvest; make opt-in the default; make extraction without consent more expensive than restraint. It can demand a supply chain for data—provenance, licensing, and the ability to revoke permission that travels wherever your data does.

But law alone will always trail the frontier. That’s why we need democratic ownership of the means of computation: the data, the models, the infrastructure. On a collectively owned platform, refusal isn’t a courtesy to be engineered around—it’s a survival rule. Consent becomes a contract we write together, enforced by charters we elect and budgets we control.

Digital democracy isn’t a metaphor. It’s clouds that serve schools, libraries, and newsrooms without auctioning their attention. It’s charters that ban surveillance resale and facial recognition, and make those bans enforceable in code. It’s unlearning budgets for when harm is found, and genuine exit rights—export, deletion, kill switches—that don’t depend on who owns the server this quarter.

We’ve lived long enough under the corporate state of the internet to know its defaults will never favor refusal. The bruise won’t fade until the constitution changes—until the people who live here also write the rules. Respect is architecture; ownership pours the concrete. Without both, “Don’t train on me” stays a plea. With both, it becomes a boundary the system cannot cross.

CommonBytes

This column explores a central question: What should technology’s role be in a world beyond capitalism? Today’s technological landscape is largely shaped by profit, commodification, and control—often undermining community, creativity, and personal autonomy. CommonBytes critiques these trends while imagining alternative futures where technology serves collective flourishing. Here, we envision technology as a communal asset—one that prioritizes democratic participation, cooperative ownership, and sustainable innovation. Our goal? To foster human dignity, authentic connections, and equitable systems that empower communities to build a more fulfilling future.

I might be a little older but I remember how the web(or interweb or net) was supposed to be open source AND free. Businesses blew the doors off that model quickly once they realized they could profit from our data.

The first webpages almost never had ads. It was rare to see when the hottest browsers was Netscape. Then came file sharing and the music industry freaked out and sued. Limewire was one such app that allowed file sharing. The lunacy was idiotic as record sales were at all time highs.

But the idea that I bought a record(or cassette tape) and couldn't share a copy with my neighbor friend was ludicrous.

And here is the crux of the larger societal issue: over time individual citizen rights have decreased and business rights increased and surpassed citizen rights. The examples could fill football stadiums. And you realize we as citizens are being conditioned to accept the loss of rights as a trade off for "public safety", "national defense" or other government causes. And people who aren't affected say "at least it's not me". Until it is then, us and no one is safe at the whims of a government run by money and financial reasons.

Meanwhile back in reality the US economy is worsening and financial equity is way out of proportion. Something like the top 10% earners have 90% of the wealth in the US.

And you ask how does that happen? I'm sure it's more complex but in my simple framework the US government and public officials in office are conspiring to keep working Americans down. The federal minimum wages is still $7.50 an hour. That's a joke by any measure.

Meanwhile businesses push the merit , hard work fallacy that says if you work hard and deserve it, you will be successful. The number of hard working people making less than $7.50 an hour can never be successful by any measure. While big business takes people who wish to form work unions to court! The irony is deep and thick. What made the US great was the middle class which was mostly people in labor unions.

It's just sick in my mind and upsetting that people fail to see their own demise.

A friend gave me their old iPhone. It took me an entire afternoon to try to disable all the telemetry and tracking and spying - and of course I am in no way certain I succeeded. I use it for podcasts and music. I never open 90% of the crap loaded on it, and I still get nag screens and popups reminding me to "sign in" and "set up" - all because Apple cares about me and wants to help me, no doubt. (?)