Can we socialize sleep?

Religious resistance to accepting evolution stands in the way.

Can we socialize sleep? Must hundreds of millions suffer?

Roughly 936 million adults worldwide are living with obstructive sleep apnea, according to a comprehensive medical review published by the National Library of Medicine. That is not a typo; with a global population of roughly 8 billion, it counts as roughly one out of nine people alive.

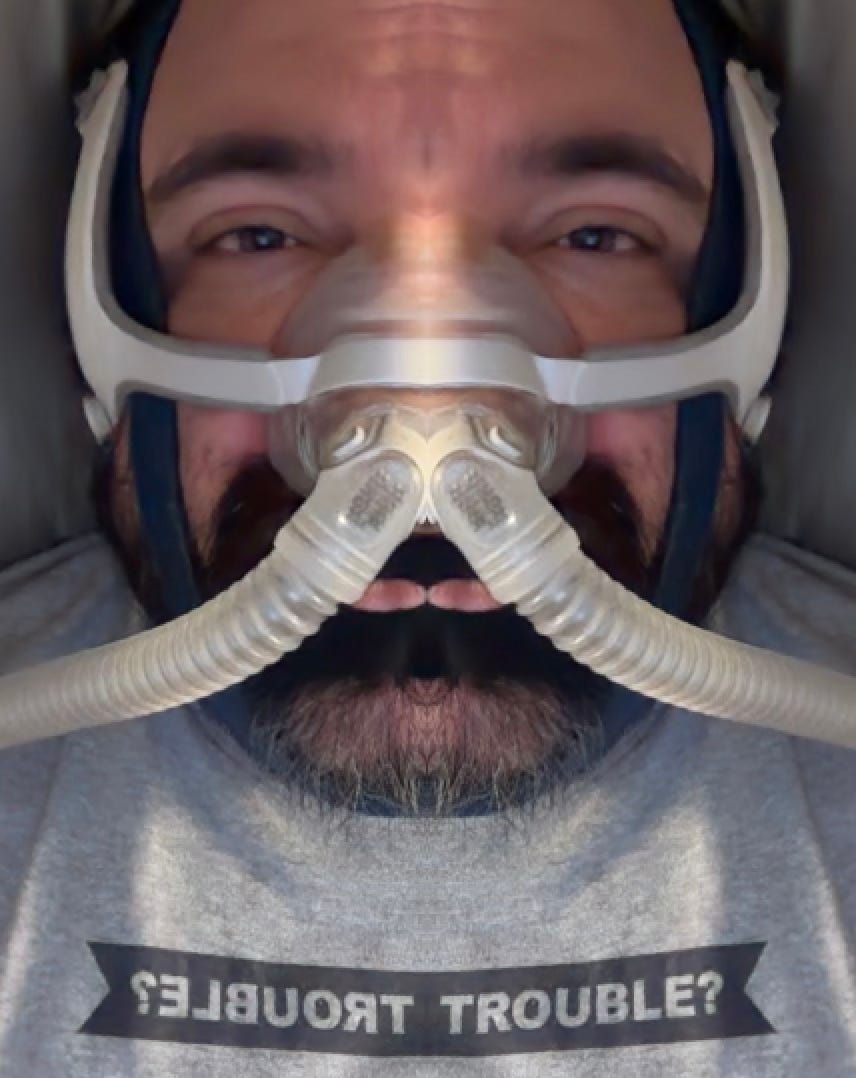

This is not a marginal statistic. Nearly one billion people experience repeated breathing interruptions during sleep that significantly raise their risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, depression and early death. When I ask the question “Can we socialize sleep?”, I am asking it on behalf of those 936 million people — myself among them — because a condition this widespread cannot reasonably be treated as an individual consumer problem.

It was with that scale in mind that I spoke in 2023 to Dr. Colin Sullivan, the inventor of the CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine. “I hope for a future where my invention is no longer needed,” Sullivan told me during our conversation. His hope is not that people stop treating sleep apnea, but that humanity eventually prevents it altogether. I admire that sentiment deeply. But until such a future arrives, Sullivan and I agree on something far more immediate: anyone who needs a CPAP should be able to afford one, along with the sleep studies and long-term medical care required to determine the best treatment. That belief brings me back to the same unavoidable question: Can we socialize sleep?

The number alone, 936 million adults worldwide, makes clear that sleep apnea is not a niche disorder. In the United States, an estimated 22 million people have sleep apnea (out of roughly 340 million, or approximately 1 out of 15), and roughly 80 percent of moderate to severe cases remain undiagnosed. Untreated sleep apnea is associated with sharply increased risks of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke and workplace accidents. When diagnosis and treatment are delayed, patients often suffer years of cumulative damage that could have been prevented with early intervention. These harms are measurable, common and deadly.

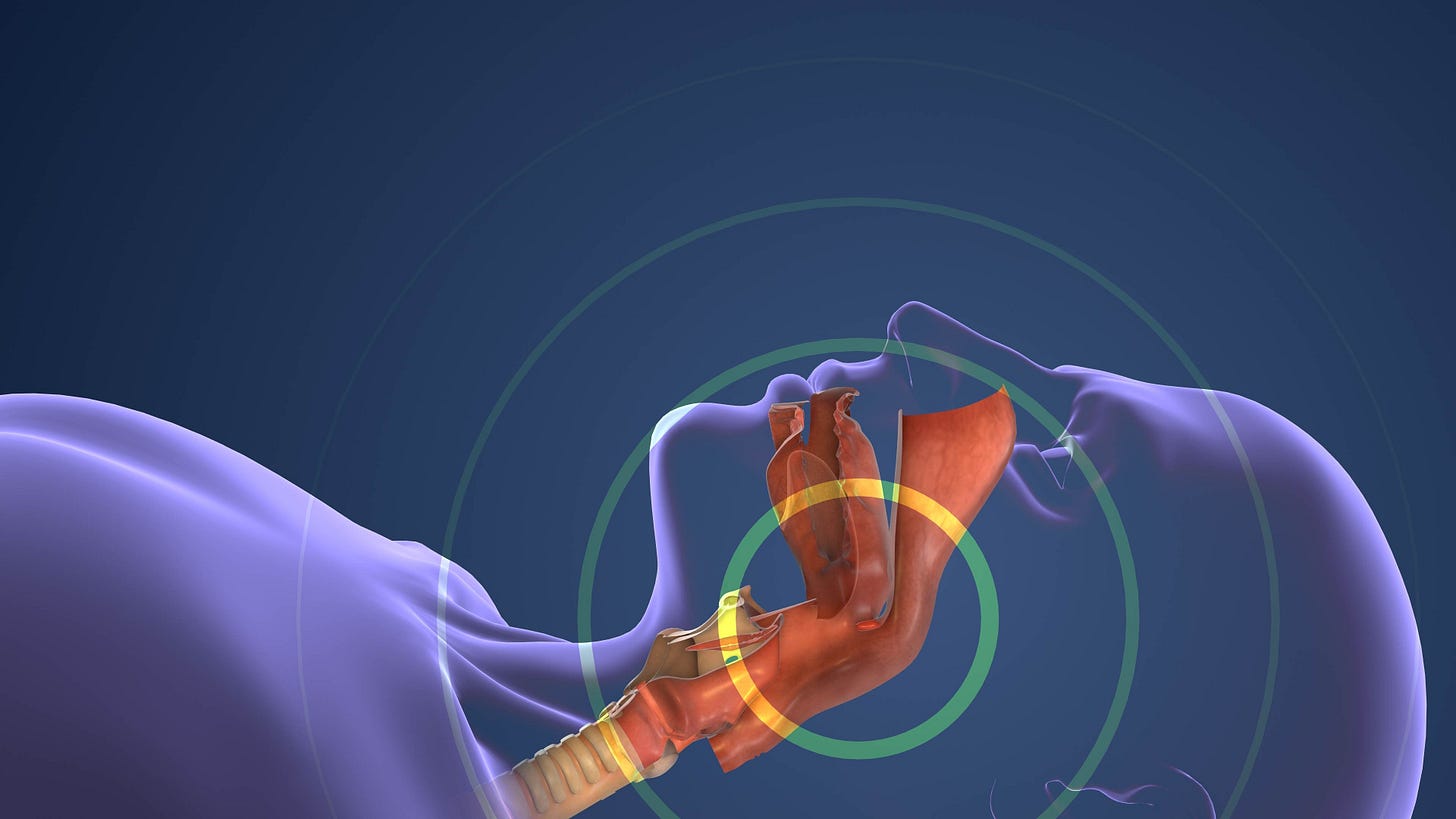

One reason sleep apnea is so widespread globally is that it is not primarily behavioral. As I reported when examining why the human neck is effectively an evolutionary mistake, modern humans evolved airways optimized for speech rather than uninterrupted breathing during sleep. This anatomical compromise makes airway collapse more likely with aging, weight gain or inflammation. Sleep apnea is therefore not a failure of discipline or willpower. It is a predictable outcome of human biology, one we are reluctant to accept for religious reasons.

I think of engineer and creationist Walter Myers III who, critiquing an article of mine maligning the human neck as proof that if God designed the body he is a poor draftsman, compared me to the discoverer of evolution, Sir Charles Darwin himself.

“Darwin made this mistake numerous times in the Origin of Species, purporting to know what God may or may not do with respect to design,” Myers wrote, “and thus arguing as to how a blind, purposeless process acts fully as a designer substitute with no evidence aside from the quite uncontroversial natural selection clearly demonstrated in the book (notably, Darwin does not even address origins).”

Because organized religions often refuse to accept the inherent imperfections of the human body, they naturally rebel against the idea of providing free health care. Yet once you acknowledge that the body is in fact the result of natural selection and not intelligent design, there is only one moral conclusion: With nearly a billion people worldwide affected by a condition rooted in their anatomy, the question “Can we socialize sleep?” becomes a matter of biological survival rather than mere political ideology.

What continues to strike me, after years of reporting on sleep and health, is how unnecessary so much suffering is. Dr. Sullivan did not invent the CPAP to create dependence on a machine. He invented it because he saw patients whose lives were being shortened night after night. I even recall how he vividly described the first apnea patient who he effectively treated with a rudimentary CPAP.

It was a hot summer night in 1980, and the 45-year-old Australian builder was so exhausted he was nearly falling off scaffolding. He had sleep apnea — a condition that causes people to struggle to breathe while sleeping — and his body was barely holding itself together due to a severe lack of quality sleep. Finally his doctors told him that he had a choice: Either punch a hole in his throat so he could breathe while sleeping, a procedure known as a tracheotomy, or become a test subject for a new machine called a CPAP, short for continuous positive airway pressure.

The builder chose the CPAP, and from July 8 to 9, 1980, he took a literally historic snooze. When the builder woke up the following morning, he remarked at how refreshed he felt. For the first time he could remember, he felt genuinely awake and well-rested. His brain fog had dissipated; his blood pressure had improved; and, perhaps most strikingly, he realized he had been rendered partially color blind from exhaustion.

When Sullivan told me he hopes his invention will one day be obsolete, he was expressing faith in a future defined by prevention, early diagnosis and structural change. I share that hope. But hope does not help the 936 million adults worldwide who are struggling to breathe in their sleep right now.

So I keep asking it, deliberately and without apology: Can we socialize sleep? Doing so would mean universal access to affordable sleep studies, guaranteed coverage for CPAP machines and supplies, long-term follow-up care and medically appropriate alternatives like dental devices, surgical implants and other forms of surgery when CPAP is not tolerated. It would mean treating sleep apnea as essential healthcare rather than a lifestyle upgrade.

“I hope for a future where my invention is no longer needed,” Sullivan told me. I admire him for imagining that world. Until we reach it, however, the humane position is clear:

We need to socialize sleep!

Back Seat Socialism

Back Seat Socialism is a column by Matthew Rozsa, who has been a professional journalist for more than 13 years. Currently, he is writing a book for Beacon Press, “Neurosocialism,” which argues that autistic people like the author struggle under capitalism, and explains how neurosocialism - the distinct anticapitalist perspective one develops by living as a neurodiverse individual - can be an important organizing principle for the left.

Capitalism + Materialism = Ratrace